Food of the Gods

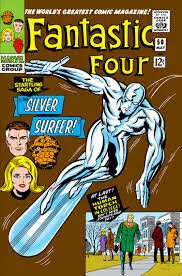

The clearest, most concise statement of the Kirby/Lee dialectic of the human and the cosmic can be found in the Fantastic Four storyline usually referred to as “The Galactus Trilogy,” which ran in issues 48-50 of the Fantastic Four (1966). The title is something of a misnomer. [1] Though it would later become a touchstone for the ever-widening scope of the Marvel universe and the more “cosmic” storylines of the 1970s, it could not have been conceived as anything more than a sequence of issues of the Fantastic Four. A modern reader encountering the trilogy for the first time might be nonplussed to discover that the first half of issue 48 is devoted to the partial resolution of a storyline involving the hidden super-powered race known as the Inhumans, who otherwise play no role in the story of Galactus. The final installment (the 50th issue) bears a cover that features the Silver Surfer, the herald of the world-eating Galactus whose betrayal of his master is a turning point in the plot. But the bottom corner show a picture of the Human Torch in civilian garb, with the label, “AT LAST! THE HUMAN TORCH IN COLLEGE! DON’T MISS JOHNNY’S FIRST DAY!”.

NEVER MIND THE DESTRUCTION OF THE EARTH—WHAT FRAT IS JOHNNY GOING TO RUSH?

Yet everything about the “Galactus Trilogy” that detracts from its trilogy status is an important part of the story’s overall point. The superfluity is the message.

The Galactus Trilogy is best understood not in isolation, but as part of a longer sequence of issues starting with number 44 (November 1965), continuing through the aforementioned “This Man…This Monster!” in Issue 51, the introduction of the Black Panther, the return of both the Silver Surfer and the Inhumans, and a battle with Dr. Doom (ending in Issue 60 (March 1967) . Even these parameters are unsatisfying, because the Fantastic Four of this era did not function according to the logic of serialization as it operates in comics today. As Charles Hatfield puts it, "The ‘trilogy,’ […] has none of the formal separateness or claims to historic importance that we might expect in the marketing of “event” series in today’s comic books. Rather, the operative mode is that of a soap opera.” “Soap opera” is a term often bandied about during discussions of Marvel comics, usually to highlight Marvel’s emphasis on interpersonal drama set against the backdrop of clashes with supervillains. Hatfield reminds us of the formal dimension of the “soap opera” comparison. If today’s editors want to make sure potential readers know when is a good time to start reading a series already in progress (such as Marvel’s “Point One” program, indicating that a particular issue is a good “jumping-on point), neither mid-1960s Marvel Comics nor televised soap operas wanted to give their audience an easy jumping off-point. Both recall the storytelling strategy of Scheherazade: hook your audience on a new plot before wrapping up the old one.

Maligned as it may be, the temporality of soap opera has one advantage over that of the stand-alone story, in that it has a greater resemblance to ordinary life. We all function in multiple “plot-lines” at the same time, with little opportunity to feel a sense of overall resolution. For those of a more theoretical bent, a stand-alone narrative fits a Freudian pattern of presence and absence: it is either there or it is not. Soap opera is more like the Deleuzian notion of “flow”: it is story as an ongoing process, with a tap that can turn it on or turn it off. Flows are messier, but this fits with one of the points made by mid-1960s Fantastic Four: humans are messier, too. And this is a mess to be celebrated.

For the Fantastic Four, who are essentially a family of adventurers, there is no clear demarcation between personal life and superhero action, or even between one adventure and another. In the mid-60s, Lee and Kirby produce a run of Fantastic Four comics whose connections are less a matter of plot dynamics than they are of theme.

This is clearly the case when it comes to the placement of the Inhumans storyline right before the introduction of Galactus, and it is telling that, when Marvel Comics outsourced some of its most visible heroes for a reboot by Image in 1996, creators Brandon Choi and Jim Lee chose to connect the Inhumans and Galactus in terms of plot (the Inhumans worship Galactus and are awaiting his arrival). Thirty years after the original stories, comics readers had a reasonable expectation of greater narrative economy.

The Inhumans, a superpowered offshoot of humanity hiding in their Himalayan Great Refuge of Atillan, were a Kirby creation that he had hoped to feature in a stand-alone comic. Instead, they were introduced in Fantastic Four, with the result that their mythos is strongly intertwined with the Fantastic Four’s world. One of the Inhumans royal family, Medusa, had previously featured in the Fantastic Four as a member of their villainous counterparts, the Frightful Four. Indeed, she and the Frightful Four were the antagonists in the story immediately preceded the Inhumans’ debut. But in issue 44, she seeks her enemies’ protection from the mysterious Gorgon (another Inhuman). The legitimate King of Atillan and Medusa’s beloved, Black Bolt, has been overthrown by his evil brother, Maximus the Mad, and Medusa had run away in order to avoid a forced marriage to the usurper.

Naturally, the Fantastic Four get involved, but not before Johnny meets a mysterious, beautiful young woman named Crystal. She, too, is an Inhuman (in fact, she is Medusa’s sister), and they quickly fall in love. The stage is set for a story of star-crossed lovers, but the stakes are much higher. Just how capacious is the definition of humanity? Or, for that matter, inhumanity? In issue 46, Reed somehow grasps the truth about these strange people he has just encountered:

Reed: “I realize now that they are a slightly different type of life which evolved without mankind knowing it—and they’ve combined all their inhuman powers for their mutual safety.”

Sue: "Then Medusa wasn’t some sort of freak—but rather part of a strange unsuspected race!”

Johnny: “Nobody can tell me that Crystal isn’t as human as any of us!”

Reed’s speculation is quickly confirmed by the Inhuman Seeker who was responsible for capturing Medusa: “You who dwell here are all the same! You think you are the only race inhabiting this planet! You never suspect that another—more powerful species might share your planet with you!”

OH, SUE!

The Seeker, like most of the Inhumans, is invested in his people’s separate identity as a species, while Johnny sees Crystal as only a beautiful young woman. But, whether by plan, accident, or due to the limitations of Stan Lee’s facility with characterization, the Inhumans and their human visitors are animated by the same concerns. Beneath the grandeur of Atillan we have familiar human drama (frustrated love, overarching ambition, pride), while the human Fantastic Four are struggling with the competing demands of superheroic adventures and fragile human relationships. While on their jet, Ben mopes about his monstrous body and his concern for Alicia, Johnny whines about Crystal, and Sue, disappointed that her new husband “has hardly been acting like a honeymooner” decides that a new hairdo will remind Reed to be more affectionate.

OH, MAXIMUS! YOU NEVER LEARN! I MEAN, LITERALLY, YOU NEVER LEARN. HOW MANY TIMES HAVE YOU TAKEN OVER ATILLAN?

Later, Reed makes his case to Black Bolt: “All we want is a chance to talk to you…to make you realize that you and your people belong in the world of men!”In the next issue, after Maximus’s baroque scheme to destroy humanity using vibrations fails, Medusa proclaims:

“Richards was right! We are not the natural enemies of the human race! We are not inhuman! We are the same as they!!!”

[…]

“For years we have hidden here, in the Great Refuge, thinking the humans would destroy us because we are a different race. But we are human, too! It is only our powers that are different!”

Maximus refuses to listen, and uses one of his weapons to enclose Atillan within a “negative zone” barrier that covers the Great Refuge in an opaque, impenetrable bubble. The Fantastic Four’s message of common humanity has been temporarily thwarted by a retrenchment into separatism, isolation, and a rejection of humanity itself. All of this causes great angst for Johnny, who can no longer be with his beloved Crystal, and will only be resolved when Black Bolt manages to destroy the barrier in Issue 59 (February 1967).

The Galactus Trilogy itself is bracketed by two homologous adventures in hidden, isolated lands; after Galactus has spared the planet, the Fantastic Four make their first visit to the superscientific, isolationist African paradise of Wakanda, home of the Black Panther. Wakanda had been at peace until a group of (white) invaders led by Ulysses Klaw killed the Black Panther’s father and tormented its people with ongoing attacks by mysterious sound-based creatures. This time, the Fantastic Four’s were invited guests rather than captives or attackers, and the aid and friendship they give to the Black Panther prompt him to look beyond his country’s borders: “I shall do it! I pledge my fortune, my very life—to the service of all mankind!” (Fantastic Four 53, October 1966). Just as Star Trek, the television series airing during the same years as this run of Fantastic Four, extolled the virtues of both humanity as a species and the common cause of peaceful peoples throughout the galaxy, so too does Fantastic Four reject the divisions between earth’s human and superhuman populations, along with the racial strife that denies common humanity.

Humanity itself is put to the test during the Galactus Trilogy, both as a species and as a way of existing in the world. The Watcher warns the Fantastic Four that the godlike Galactus is on his way to earth in order to consume it, preceded by his herald, the Silver Surfer. Over the equivalent of two issues spread out over three, our heroes confront the futility of trying to operate on a cosmic scale, while the Silver Surfer learns about the beauty of humanity. The Watcher leads the Human Torch on a scavenger hunt in Galactus’s Ship, allowing him to find the Ultimate Nullifer, a weapon that frightens even Galactus. Galactus yields, swearing never to try to eat the Earth again (like many a dieter, he will waver frequently in his resolutions). Before leaving, Galactus punishes the Silver Surfer for his rebellion, banishing him to Earth.

THANK GOD SOMEONE FINALLY GAVE GALACTUS SOME PANTS

The fight against Galactus is a confrontation between two incompatible scales of existence: the human and the cosmic. Long after Galactus’ introduction to the Marvel Universe, he will serve as a shorthand for heroes fighting out of their league; one might argue that pitting him against Dazzler (a disco-inspired hero who makes light shows) and Squirrel Girl (who talks to squirrels) reduces Galactus’s impact, but the opposite is also true: holding their own against Galactus elevates the undergo hero, if not to godliness, than at least to a more exalted heroic status.

FIRST I WAS LIKE “WOH!” AND THEN YOU WERE LIKE, “WOH!” AND THEN I WAS LIKE, “WOH!”

Douglas Wolk cites the Galactus Trilogy as a “defining moment” for the Lee/Kirby Fantastic Four, introducing the element of the sublime that would become essential to subsequent “cosmic” events. Once the Inhumans are dispensed with, Lee and Kirby switch the scene to outer space, introducing the Silver Surfer by showing the terror he inspires in the hearts of the Skrulls, an aggressive alien race introduced earlier in the series. Then we see the cities of New York coping poorly with the apocalyptic omens that the Surfer (for reasons that are not entirely clear) sets in motion (the sky appears to be on fire). The FF can do nothing about the problem in the heavens, so they immediately set about cleaning up the mess provoked on the earth below, calming and occasionally fighting New Yorkers who have run riot. Kirby spends an entire page on a thug punching the Thing (to no avail, of course), and then collapsing into unconsciousness when Ben flicks one of his stony fingers at him. It’s a small moment, but that is probably the point: this is the last time Ben’s physical violence is going to be effective before the story is over.

NEVER PICK A FIGHT WITH A GUY MADE OF ORANGE ROCKS

Indeed, the Fantastic Four cannot succeed in direct conflict with Galactus. As the world-devourer and the Watcher debate each other in a full-page spread on the second page of issue 49, Reed remarks: “See how he ignores us…as though we’re of no consequence!” Ben tries and fails to get Galactus’ attention, eventually punching him in the shin; Galactus responds with a smoke bomb that Reed calls “a type of cosmic insect repellant!” Johnny trains all his flame onto Galactus, prompting him to extinguish Johnny’s flame as he remakes, “You puny human gnats can be more annoying than I had supposed!” Reed is too smart to bother attacking, while Sue is typically too passive to do more than ask questions (“Can it really be? Does he actually mean to attack the entire human race?”)

I LIKE IT WHEN MY WORLD-DEVOURERS SHOW A LITTLE LEG

In the absence of any hope of a successful straightforward confrontation with Galactus, the Fantastic Four instead indulge in the kind of conflict at which Lee excelled: petty interpersonal sniping. In issue 48, before Galactus arrives, Sue is miffed that Reed is ignoring her, in a scene that could easily have been avoided if he had bothered to take his wife and teammate into his confidence:

“What does Reed expect me to do while he locks himself in his lab for hours on end?

“The flame sin the sky are gone! The danger seems to be over! You’d think he’d remember this wife!

“Even Mrs. Reed Richards might like to be taken out to dinner once in a while.”

…

“Well, I’ve no intention of being completely ignored while he juggles those test tubes of his for the rest of the night.

“Reed! Look at you! You haven’t even shaved! And you must be starved!”

“For the love of Pete, girl! Is that what you disturbed me for?”

“Disturbed you??! All I wanted was—Oh! He broke the connection!”

But the very next issue, Sue’s approach wins out. Johnny returns from his humiliating defeat by Galactus, covered in the soot that somehow has formed after his flame was extinguished. Once again, one of our heroes laments his insignificance: “I just realized how a mosquito must feel when someone swats it! Galactus made a monkey out of me!” For the record, this is already the fifth and sixth times the FF have been compared to animals and vermin in the seven pages since Galactus appeared (“gnats”; “insect repellant”; “insects”; “gnats”; “mosquito”; “monkey”). Sue’s response to Johnny is typically maternal (“In the meantime, why don’t you get cleaned up?), but it is a sentiment shared by Ben and Reed. In the next panel, Johnny walks in on his two teammates in the bathroom (probably the first bathroom scene in Marvel Comics history). Ben is in the tub while a shirtless Reed shaves:

THE FANTASTIC FOUR NEED THE FAB FIVE

Johnny: “What’s with you guys?? Galactus is planning to tear our planet apart, and you’re makin’ like a TV shaving commercial!!!”

Ben: “Relax, Johnny! We been tryin’ to cook up a plan!”

Reed: “No harm in tidying up while we’re thinking, is there, lad? You could use a shower yourself!"

Reed has made a complete reversal from his unshaven, disheveled hermit’s desperation in the previous issue, and for good reason: in the absence of the raw power needed to defeat Galactus, these issues demonstrate that the only weapon in their possession (so far) is their basic, prosaic humanity.

This single page of grooming is followed by eight pages devoted to eating, using the contrast between the food habits of cosmic beings and the culinary rituals of ordinary humans as the lynchpin for the story’s argument about the value of humanity. Thanks to the power of comic book coincidence, the Silver Surfer, knocked off the roof of a building by the Thing in a previous issue, has fallen through a skylight into the apartment of none other than Alicia Masters, Ben Grimm’s blind sculptress girlfriend.

Alicia typically plays a similar role to Sue Richards—asking questions, emoting, and occasionally needed to be rescued—but her “superpower” is the perfect complement to that of the Fantastic Four’s sole female member. Where Sue can turn invisible, Alicia is blind, but in the quasi-mystical way that this disability is so often utilized in popular narrative: unable to perceive the visual spectrum, she nonetheless “sees” essential truths better than those without visual impairment. It’s a cliché, of course, and deeply offensive to real people with real disabilities, but it is a trope that serves double duty. First, it enables Lee’s worst narrating habits, providing yet another reason for a character to verbalize what is happening right before the reader’s eyes. Second, her insights spark a crucial transformation in the Silver Surfer.

NEVER HAVE I SENSED SUCH…EXPOSITION!

Alicia spend much of page 7 telling readers how they are supposed to feel about this mysterious new character:

Alicia: “I’ve never heard anyone speak so…so strangely! And yet, there is a certain nobility in your voice!”

Surfer: “Nobility? The word has no meaning to me!”

[—]

Alicia: “Your face! Never have I sensed such unimaginable loneliness in a living being!”

Flustered, Alicia tries playing hostess:

Alicia: “Perhaps you are hungry? Let me give you something to eat, while I try to understand what you’ve been saying.”

Surfer: “Hungry? Eat? Can it be that you actually consume these foreign morsels?

“Galactus is right! The mysteries of the universe are truly without limit!”

While the Surfer contemplates the enigma of mid-afternoon tea, his master decides to serve himself. The last panel of page 7 is a picture of Alicia setting the table, while the first panel of page 8 show Galactus assembling a giant machine on top of the Baxter Building in order to turn the earth into his next meal: “Soon my preparations will be completed…. / And then the planet will furnish me with all the energy I need…until I have stripped it of everything!” Over the next two pages, the Watcher shows the Fantastic Four the fate that awaits their world. Galactus’s “elemental converter” will convert the oceans into “pure energy”, whereupon its ray will “reduce the entire globe to a lifeless, empty husk.”

WORST. HOUSE GUEST. EVER.

Meanwhile, the Surfer is already consuming a similar feast, but on a much smaller scale:

“The process you call eating is far too wasteful!

“How much simpler it is to cover all those items into pure energy! For energy alone is…power!”

[…]

“And the objects in this room…pictures, bits of sculpture, decorations…they are all wasteful!

“Before the great Galactus is done, everything shall be reduced to sheer energy!”

The problem here is not that the Surfer is wrong, but rather that he misses the point entirely. Reducing everything to energy is efficient, but it also negates specificity, context, and pleasure. The only difference between the Surfer’s reduction of the food to energy and taking a gourmet meal and flushing it directly down the toilet is that the latter provides no caloric content. The Silver Surfer, and by extension, Galactus, are the epitome of the impulse to cut to the chase: why have matter when you can have energy? Why have the moment, when you can jump to the end point? And why have pleasure, when it is fundamentally irrelevant? The entire material world is reduced to an object of digestion.

It is telling that, among the many objects the Surfer atomizes are Alicia’s sculptures: the Surfer’s world view has no room for art, or, indeed, for aesthetics of any kind.[2] Alicia accuses the Silver Surfer of intending to destroy the earth, to which he responds: “Destroy is merely a word! We simply change things! We change elements into energy…the energy which sustains Galactus! For it is only he that matters!” Alicioa’s protest is based on ownership ("This is our world! Ours!”) and emotion:

“Perhaps we are not as powerful as your Galactus…but we have hearts…we have souls…we live/..breathe…feel! Can’t you see that?? Are you as blind as I?”

Overcome by “this strange feeling… this new emotion…”, the Silver Surfer comes to a revelation: “At last I now…beauty!"

Alicia implores the Surfer to look out the window at the city below them: “Look at the people! Each of them is entitled to life…to happiness…each of them is…human!”

Surfer: “Human? What can that word mean to me?

“And yet, never have I beheld a species from such close range! Never have I ever felt this new sensation…this thing some call…pity!”

Lee’s incessant abuse of ellipses is Shatneresque, and Surfer’s transformation is given barely more than a page to unfold, but the basic argument is a more flowery corollary to the earlier Fantastic Four bathroom scene: the cosmic scale of godlike beings threatens to completely eclipse our own ordinary world (indeed, to swallow it whole), but the mere fact of the sublime must not be permitted to negate the mundane.[2] The Lee/Kirby formula of Marvel comics is a delicate balance between the super and the human, with both aspects proving essential to the line’s success. The Galactus Trilogy, by confronting our fantastic heroes with a far more fantastic adversary, doubles down on the human in order to serve as Marvel Comics’ implicit thesis statement: Marvel functions best when it finds the balance between the prosaic and the extraordinary, between interiority and action, between the human and the superhuman.

If any story has earned the right to be resolved by a deus ex machina, the Galactus Trilogy is it. The storyline would lose its focus if the Fantastic Four could, on their own, prove to be credible opponents to a god from outer space. The Watcher, who functions on the same level of Galactus, sends Johnny on a hallucinatory journey through space, guiding him to Galactus’s ship so that he can steal a weapon. The Human Torch is out of his depth; when he returns, all he can tell his teammates is “I travelled through worlds…so big…so big..there…there aren’t any words!” Followed by the inevitable vermin metaphor: “We’re like ants…just ants!…ants!!” Following on the heels of the Silver Surfer’s own conversion to melodramatic humanism, it’s a statement that could be a step backwards. But the weapon Johnny brings back works by placing Galactus in the same position he has put humanity. Reed threatens his opponent with the “ultimate nullifier,” which makes Galactus recoil in terror:

“In the name of the eternal cosmos…put it down!! Your feeble mind cannot begin to comprehend its power!! You hold the means to destroy a galaxy…to lay waste to a universe!”

Now that Galactus faces the prospect of nullification, his insults take an intriguing metaphorical turn. He tells the Watcher “You have given a match to a child who lives in a tinderbox!” His rhetoric is still insulting, true, but a child is several steps above vermin and animals, and has the potential to mature into an adult. Which is the point the Watcher is trying to make: give humanity time to grow and evolve.

Notes

[1] Here I concur with Charles Hatfield, author of the definitive monograph on Kirby, Hand of Fire. Hatfield writes: "Tellingly, it isn’t so much a cohesive trilogy as three months’ worth of issues placed within a larger continuity. Fantastic Four #48 actually begins with the resolution of the Inhumans storyline launched several issues earlier, while #50, though titled “The Startling Saga of the Silver Surfer,” resolves the threat of Galactus halfway through, quickly ushers off the Surfer, and then concentrates on domestic happenings in the lives of the FF”

[2] Why read a comic when you can read the Wikipedia summary ?

[3] How appropriate, then, that the Silver Surfer’s next appearance will have him escaping from Galactus by shrinking to subatomic size.