New Ears Have Arrived

Gerber’s Marvel output included comics that put the superhero front and center. His earliest work on The Sub-Mariner (58-69) (1973-1974) displays few of what would eventually be Gerber’s hallmarks; he was initially scripting from other people’s plots, and even when he became the sole writer of record, his stories were unremarkable. [1] His Daredevil run (97-101, 103-117) (1973-1975) began on a similar trajectory, but here, at least, he made some gestures in the direction of social commentary (the gender and racial politics of Mandrill’s revolutionary, vaguely anti-capitalist Black Spectre organization). [2] Only in The Defenders (20-29, 31-41, Annual 1, Giant-Size 3-5) (1975-1976), a book whose misfit characters are part of a “non-team” that Gerber would later liken to an "encounter group,” would Gerber successfully put his mark on a superhero book. [3]

Whether it was the result of lifelong reading habits or the simple exigencies of comic book publishing, Gerber was at his best when superheroes, heroic fantasy, or the supernatural were a given, but not necessarily the main concern. Decades later, writer Kurt Busiek and painter Alex Ross would have a hit on his hands with Marvels, which told the stories of the Marvel Universe from the point of view of ordinary people who happened to intersect with the drama at various points (Busiek would further refine this formula in his creator-owned Astro City series). But this is not quite what Gerber was doing. For one thing, few of his characters, even the non-powered ones, could quite count as “ordinary”; for another, his protagonists tended to be part of the overall weirdness of the superhero/fantastic world. They differed from the standard hero in plot (they tended to join the battles reluctantly) and, most important, in perspective: though superhero conflicts often drove the action, Gerber’s viewpoint characters looked on these entanglements with bemusement, resignation, or outrage.

The tag-line for Howard the Duck, Gerber’s most famous creation, was “Trapped in a world he never made!” In Howard’s case, the line’s applicability was clear. He was a talking duck in a world of humans (or, as Howard always called them, “hairless apes”). Perhaps the early success of the Howard the Duck comic was because it so clearly distilled the essence of most of Gerber’s Marvel work. All of his characters were “trapped in worlds they never made,” but, in most cases, the nature of their dilemma was not immediately apparent, because the conflicts were all internal. Gerber’s heroes are alienated. Other Marvel characters are alienated, too, though they might desperately wish to belong (the original X-Men, for example). Howard externalizes the problem so clearly that, in the hands of lesser writers (some of whom worked on HTD after Gerber’s departure), there is little need to pay attention to the character’s inner life: the duck among humans can function allegorically based on the visual discrepancy alone. But for Howard, being the only talking duck on Earth is not the true source of his depressive, world-weary skepticism; it is simply the visible representation of a pre-existing condition. [4]

Gerber's characters (and plots) are built on their continual discomfort with their surroundings, their nagging sense that either they are not where they should be, or that something is wrong with the world around them. The plots are an excuse for commentary and critique that unfold on three levels. First is the generic: there is something fundamentally bizarre about the superhero world, as we see particularly in Gerber’s riffs on Superman (the childlike, alien Wundarr; Omega the Unknown) and the last year or so of his time on The Defenders. Second is social, which often runs the risk of being preachy, simplistic, or dated (the “Quack Fu” and SOOFI issue of Howard the Duck (3 and 20-21, respectively)); virtually any political or environmental topic in Man-Thing). The third is existential: take away the other two, remove all obvious obstacles, and the heroes are still mismatched with the worlds around them.

This third level is facilitated by the most distinctive aspect of Gerber’s work. The real stars of his comics are not characters, but frameworks: perspectives, points of view, and, especially, voice. He is not wordy like McGregor, nor does he usually favor the first-person narrations used so well by Moench, but Gerber’s comics have no room for silence. The voice and viewpoint must be maintained at all times.

The persistence of voice is demonstrated most clearly (and cleverly) in the last pages of Howard the Duck 11. Half of the issue is a methodically-developing farce on a bus ride to Cleveland, featuring Howard’s misery as a parade of eccentrics refuse to leave Howard in peace. As Howard engages in a fist fight with his nemesis, the Kidney Lady (more on her later), a tire blows out, and the bus careens of the road. Howard laments that the last thing he’ll see in life is the Kidney Lady’s face:

“And yet…it could be worse.

“I man…what if I’d hadda watch my whole life flash before me?

“Now that would b—“

Howard never finishes the thought, interrupted by the sound of the crash. Suddenly, a third-person narrator appears for the first time that issue:

“Does a bus scudding off the interstate amid billows of dust and smoke make a sound if no one is present to hear it?

“Yes.

“And it’s disgusting.

“However, when the clouds of vapor disperse, all is ominous silence…

“…but the smell makes up for it.”

Then, on the top of the next page:

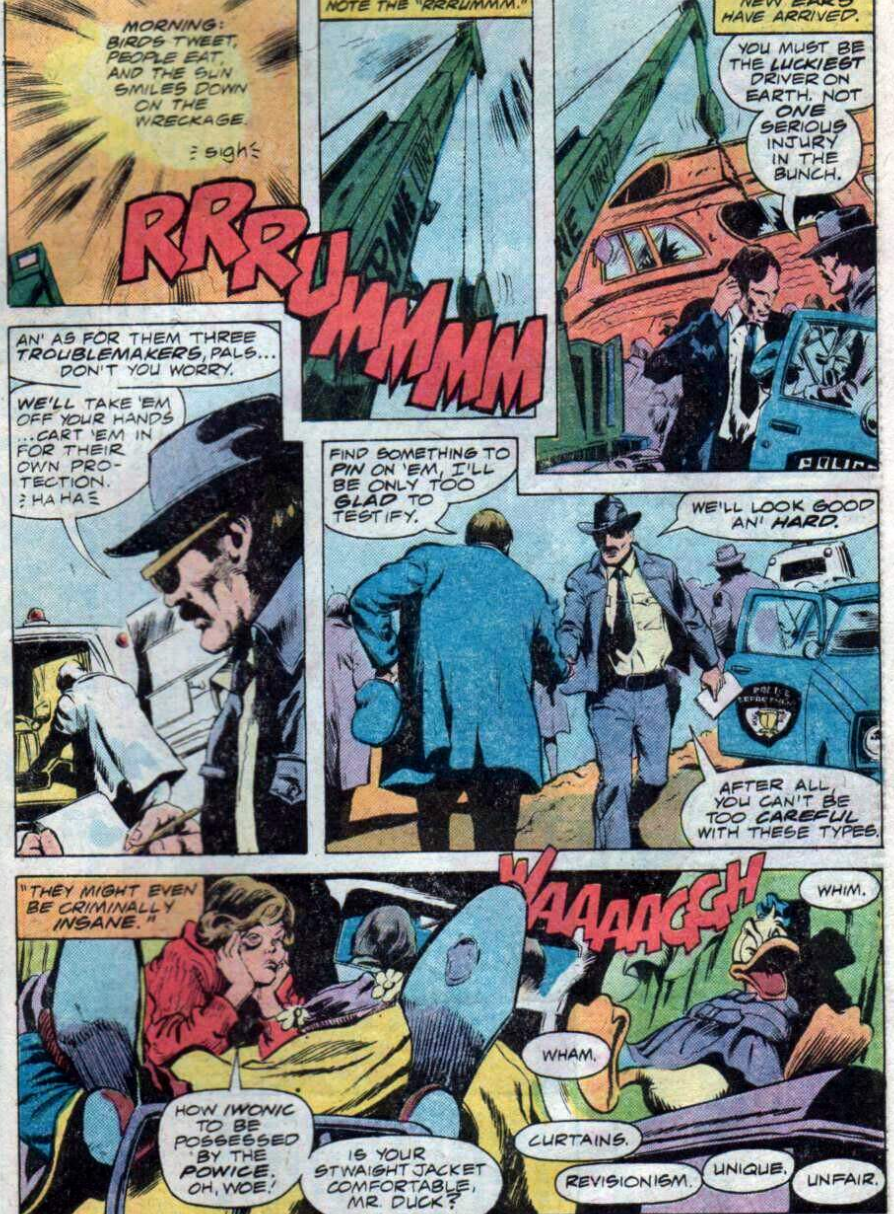

“Morning. Birds tweet, people eat, and the sun smiles down on the wreckage. <sigh>.”

Colan provides a huge sound effect: “RRRUMMMM”

“Note the 'RRRUMMM.’

“New ears have arrived.“

At which point we hear a cop talking to the driver. Only when their “ears” have arrived can the narrator finally stop talking.

With Howard (and everyone else) unconscious, the burden of sardonic narration simply had to be picked up by someone. Events could not be allowed just to happen without the expression of a bemused opinion. The narration plays with the old cliché about a tree falling when no one is there to hear it, but the circumstances that lead to its invocation suggest that we understand it slightly differently: if an event happens and no one is there to comment on it, has it really happened?

Comics are, of course, a visual medium, as Gerber was acutely aware. But it was nonetheless a medium that was primarily the vehicle for his authorial voice. He could only hope that if he spoke engagingly enough, new ears would arrive.

Notes

[1] Their primary significance was as part of the Atlantean cosmology he wove into both his Son of Satan and Man-Thing stories, centering around the sorceress Zhered-Na.

[2] From Daredevil 111: Daredevil remarks that that Mandrill “figures that hatred of anyone who’s different is part of the way of life in America… and that the only way to change that is by seizing control… running things his way.”

Shanna the She-Devil responds: "You don’t sound sure that he’s wrong!”, to which Daredevil only says, "Don’t make me get philosophical, Shanna.” After the Mandrill’s defeat, Daredevil is unsettled and a bit depressed. Note that all of this is unfolding at the same time as Englehart’s “Secret Empire” storyline in Captain America.

[3] "The Defenders were an encounter group--a bunch of quirky, contentious individualists with almost nothing in common, thrown together by circumstances (and editorial fiat, of course) and forced to confront not only a common enemy but also each other. Of all the books I did at Marvel, DEFENDERS was probably the most fun to write. Each of the characters was so different from all the others that stories could come from at least five different directions--or just out of the blue.” Interview with John Dalton. http://www.b-independent.com/interviews/stevegerber.htm

[4] This is one of the many reasons that the post-Gerber introduction of Howard’s home planet (“Duckworld”) was such a mistake. It suggested that somewhere out there is a land where Howard can be content.