The Drake's Progress, or Howard and the Everyday Picaresque

Howard's repeated rejection of the fight scene has a positive corollary: the issues of Howard the Duck that best realize the books's sensibility are the ones with almost no plot at all. Gerber may have been reluctant to put the duck in typical superhero battles, but this does not mean that the book avoided conflict. On the contrary, Howard either invites or falls into conflict with virtually everyone he meets. The trick was getting Howard to meet them, and that is what the plot was primarily for.

While even the more action-oriented issues (such as the "Quack Fu" story in Issue 3) rely on chance encounters and coincidence, the stories that are virtually action-free function according to a metonymic logic: Howard runs into X, whose proximity to Y involves the duck in yet another absurd situation, leading onward to Z. Though not exactly a picaro--Howard's moral standards are too high to make him a rogue, and he undergoes actual character development--Howard the Duck in general, and the action-free stories in particular, approximate the structure of the picaresque novel . The hero is witty but generally down on his luck, the satire is pervasive, and the plot tends to be a set of episodes whose connection to each other is only tenuous. In an already serialized format, Howard's stories feel serialized even within a particular issue. The plots may get from point a to point B, but point B never felt much like a particular goal. A and B just happen to be neighbors on in the alphabet.

Gerber wrote four meandering issues of Howard the Duck that were driven entirely by associative logic: Issues 5 "("I Want Mo-o-oney!"), 11 ("Quack-up!"), 19 ("Howard the Human"), and 24 ("Where Do You Go--What Do You Do--The Night After You Saved the Universe?"). We already discussed "Quack-up" in the very beginning of the chapter, but the others bear some examination.

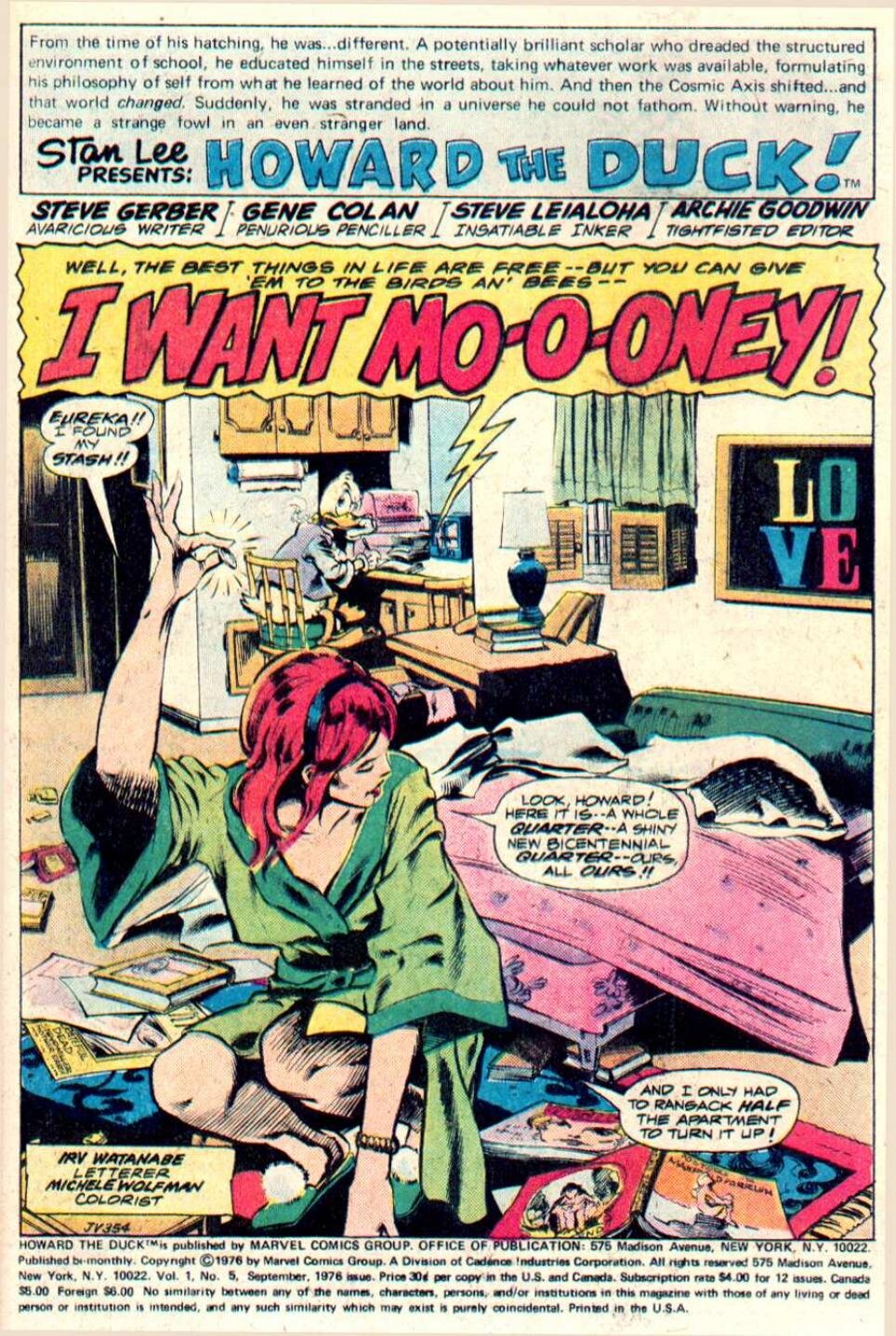

Even the title of Issue 5 looks like a matter of happenstance or free association; the title, "I Want Mo-o-oney!", is just part of the lyrics of a Beatles song playing on Beverly's radio. But it also describes Bev's and Howard's plight--Beverly is thrilled that she found a "whole quarter" after ransacking half the apartment, when even the comic she appears in cost thirty cents at the time. Their poverty provides the initial motivation, propelling Howard out of the apartment to store so that they can "feast by candlelight on two Snickers!"[1] As Howard moves from place to place, however, the story's real concerns take shape: the place of imagination, entertainment, and the media in our multiply impoverished lives.

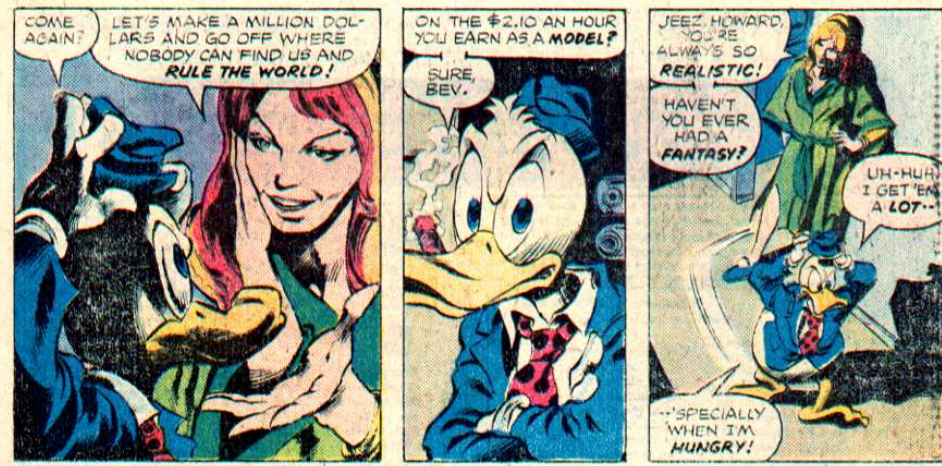

Bev sets the tone when she grabs Howard before he can head to the drugstore:

"Howard--wait! Let's get rich!"

Howard: "Come again?"

Beverly: "Let's make a million dollars and go off where nobody can find us and rule the world!"

Howard: "On the $2.10 an hour you earn as a model?

"Sure, Bev.

Beverly: "Jeez, Howard. You're always so realistic! Haven't you ever had a fantasy?"

Howard: "Uh-huh. I get 'em a lot--

"'Specially when I'm hungry!"

That exchange exemplifies the irony of so many HTD stories: a realistically drawn human woman accuses a walking cartoon duck of being too realistic. Howard immediately regrets snapping at Bev, but it is as though their brief conversation had cursed his wanderings. From the moment he leaves Bev's apartment, he is confronted with one unsatisfactory kind of entertainment after another. And while no one can claim to be a critic from a completely impartial stance, Howard ends up personally implicated in each of these incidents, primarily because he is a duck.

At the drug store, Howard flips through an issue of a comic called "Quackie Duck" (a Daffy Duck pastiche to contrast with Howard's Donald), and is outraged at the simplistic plot that shows a clever cartoon duck luring a dumb cartoon bear to its death.[2] In a fit of fury at this "unfair representation of ducks," Howard throws the comic to the floor, and is then obliged to spend more than half his money on it. In one of the most metafictional moments in the story, he hands the tattered comic to Bev, whose reaction is: "A comic book? I don't get it." In other words, the reaction of the many readers who were left confused and unmoved by the Howard the Duck comic itself. Howard's response is equally apt: "Don't just look at the pictures! Read!"

At the same time, Howard hears on Bev's radio that station WDUM's listener call-in line is now open, and decides to use the opportunity to rail against Quackie Duck (a stations staffmember refers to Howard as "some nut who says comic books are quote 'promulgating racist myths and perpetuating prejudice’"). But when Howard explains on the air that he himself is a talking duck, he is cut off. Howard asks Beverly: "Ya figger I came off too shrill, or what?" to which Bev replies 'Nah./ But maybe you should try a more visual medium."

Once again, Beverly's dialogue points us to the story's structural device: Howard will spend this issue moving from one medium to another (which, as any viewer of the disastrous 1996 Howard the Duck movie knows, never goes well for him). Beverly is right, of course: radio is hardly the place to leverage Howard's unusual appearance, just as she is also not wrong in her inadvertent demonstration of how not to read a comic--misplaced expectations of what a duck comic should be never were helpful to the book. But when Howard arrives at the local television studio, his is nonplussed at being misunderstood yet again. The receptionist, rather than evince the usual surprise, says "Oh. The New Duck," prompting Howard to think "Some visual medium! They don't even look atcha when they talk to ya!" Howard finds himself cast as "Dopey Duck" on the "Gonzo the Clown: show, and promptly starts a melée. The children in the audience love it, which is no surprise to Howard: "If that's the standard intellectual caliber of the entertainment you feed 'em." Trapped in a kiddie genre, Howard, for once, acts like an action hero, punching the clown who threw a pie in his face.

For Howard, the fight is allegorical ("So I escaped with my dignity and did my part in the crusade to improve children's TV"). It also leads to opportunity. Back on the street, he pauses before to watch the Gonzo the Clown fight continue live on a television in the display window of "E-Z Credit Appliance." The boss, who hates Gonzo, recognizes Howard and immediately gives him a job calling customers who are behind on their payments. Howard has switched media once again, this time working on the telephone, but the distraught reaction of the first customer he contacts leads him to make a home visit. The customer is a mother of four children (who are sitting in front of the TV, still watching Gonzo), and the television is the one good thing in the kids' lives. Howard tears up her contract and quits his job.

This particular episode switches the focus from television-the-medium to television-the-object, confronting Howard with the exploitative economics behind this aspect of the entertainment business. It's worth noting that while Howard was wrestling his conscience, Beverly made dinner money modeling for artists. She works in the service of a simpler, face-to-face medium (visual art on paper) where any exploitation is readily apparent. And it is Beverly who draws his attention a newspaper ad (yet another medium!) offering $10,000 to "any man" who can last three rounds in wrestling ring with the current champion (an in-person encounter). The wrestling match provides the "obligatory comic book fight scene," as well as just enough cash to get Howard and Beverly out of Cleveland (Howard is cheated out of the promised reward because he is not, technically, a "man").

Howard the Duck 5 ends with a geographical escape, but does nothing to resolve Howard's attempts to grapple with other media. Though his odyssey beings with his mutilation of a subpar children's comic, it ends with his ejection from very other medium with which he engages. Marvel Comics of the 1970s may be dominated by annoying tropes and frustrating limitations, but for Howard, there is no way out. He is trapped in a medium he never made.

Notes

[1] The quarter is not the only change that Bev has found; Howard leaves the house with fifty cents, which would have been enough for two Snickers and ten cents in change.

[2] The bear's demise resembles that of Le Beaver four issues later. No doubt this is mere coincidence, but it highlights Howard's own moral code not only through Howard's outrage, but because the Le Beaver's death is an accident.