The Panther’s Two Bodies

As king of Wakanda, T’Challa is more than just an individual man. In The King’s Two Bodies Ernst Kontorowicz advanced the thesis that, in medieval Europe, the monarch had both the “body natural” (i.e, that of an ordinary human being) and the “body politic” (a symbolic, non-corporeal phenomenon that neither ages nor dies, but inhabits the flesh worn by a given king during his lifetime). The context is, of course, Christian, which hardly seems appropriate for the worshipper of a panther god, but then, none of T’Challa’s writers were ever his coreligionists. When his adventures are chronicled by writers and artists of at least a nominal Christian background, Christian symbolism tends to make itself available.

Placing Kontorowicz in a context that he would doubtless fine objectionable, we can see the two bodies as more than just Christological. In having both an ordinary and a supernatural body, Kontorowicz’ king is something of a superhero. Rather than swapping a secret and masked identity in complimentary distribution, the king is simultaneously man and superman. The drama of both the king and the superhero is one in which duty must overcome passion. A good king puts his country’s interests before himself, like Peter Parker or Clark Kent sacrificing their personal lives on the altar of Great Responsibility. A bad king is selfish and self-indulgent, lacking in empathy for those who suffer. A bad king is a supervillain.

Before McGregor, T”Challa’s writers tended to treat King T’Challa as the perennially neglected secret identity of the Black Panther, hero and Avenger. In these stories, it is not just that the two identities are no longer occupied simultaneously (as they are in the person of the medieval king); they are separated geographically. Though The Avengers would occasionally show the Black Panther dropping by the Wakandan Embassy or fighting an African villain who happened to be in town to take in a Broadway show, T’Challa was an absentee king. Eventually he would be so rooted in his New York self-imposed exile as to take on still another identity: Luke Charles, schoolteacher.

Rather than sweep the problem of T’Challa’s lackadaisical history as a monarch under the rug, McGregor makes it central to the plot of his first extended storyline. Though it is called “Panther’s Rage,” T’Challa actually spends relatively little time in a state of fury. Instead, the rage is what greets him upon his arrival, surrounds him through almost the entire story, motivates his antagonists, and threatens the future of his country. All of this rage could have been avoided had T’Challa simply stayed home. Wakandan advanced technology could presumably have enabled T’Challa to run his country remotely with a fair amount of efficiency, but that was not the point: Wakanda needed the Black Panther not just in spirit, but in body.

Intentionally or not, with “Panther’s Rage” McGregor established the master plot for so many stories set in Wakanda: unity and prosperity are threatened by inner strife (often encouraged by a malign external presence). [1] A rebellion is being waged by a new antagonist, Eric Killmonger, while even some of T’Challa’s closest advisers now doubt his fitness to rule. This is the context in which I propose we try to understand the bodily torments T’Challa endures over 13 issues: his physical body is also a sign of the suffering political body that is Wakanda. He is beaten by Killmonger’s spiked weapon, mauled by his pet leopard, and thrown over Warrior Falls (an allegorical name if I ever heard one) (Jungle Action 6); thrown into a fiery pit and mauled by wolves (Jungle Action 12); beaten to a pulp by white gorillas (Jungle Action 13); mauled by a t-rex (Jungle Action 14); tied to cacti and left to die , only to be “rescued” by a pterodyctyl that drops him onto another set of cacti, only to “rescue” him again at the last minute; choked nearly to death by snakes (Jungle Action 16); and dragged over a rocky dessert by the two leopards to which he is chained (Jungle Action 18). If nothing else, T’Challa certainly bleeds for his country.

Unlike Killraven (although a bit like Luke Cage), T’Challa’s sense of selfhood is conveyed from an intellectual distance combined with a visceral closeness. The narrator only shares consciousness with the hero when the Panther is suffering, and in those moments the text is primarily about his physical pain and his resolve to overcome it. Unless it is a matter of watching T’Challa formulate a plan to survive an attack, we do not get a window into his actual thought processes, even though the narrator of Jungle Action is quite willing to follow Monica’s train of though on more than one occasion. Is this a case of white male fetishization of the suffering black male body? Given the similar example of Luke Cage, this is a proposition that is difficult to dispute. But even if this is the case, I would argue that fetishization alone does not explain it, or that this fetishization opens up other narrative and thematic possibilities in addition to the racial context.

T’Challa’s selfhood is diffuse and scattered because of the multiple roles integral to his identity, and because of the ruptures in the fabric of his country and the incompatibility of the personal and political demands and desires that focus on his person. By daring to love an outsider (Monica), the Panther is challenging his inward-looking people to accept a relationship with the outside world made literal by the relationship between Wakanda’s king and and American woman.[2] The resentment of Monica is xenophobic, pure and simple, and in a number of instances (such as Monica’s interactions with Kantu’s mother), that explanation seems close to enough. But she is also a warning to T’Challa’s subjects that his attention is easily drawn elsewhere.

Overall, McGregor’s Panther is competent, powerful, and noble, which makes the first chapter of “Panther’s Rage” so radical: Issue 6 is a catalogue of T’Challa’s failures. The splash page, which shows the Panther leaping into action, tells us that T’Challa had only returned recently: “A moment before, he was re-communicating with this land that is more than his in name, re-establishing the link that has weakened since his absence from his kingdom!” He beats Killmonger’s men, Tayete and Kazibe (who rapidly become figures of comic relief for most of “Panther’s Rage”), but he is too late to save the loyal old man they had been tormenting. With his dying breath, the man tells T’Challa:

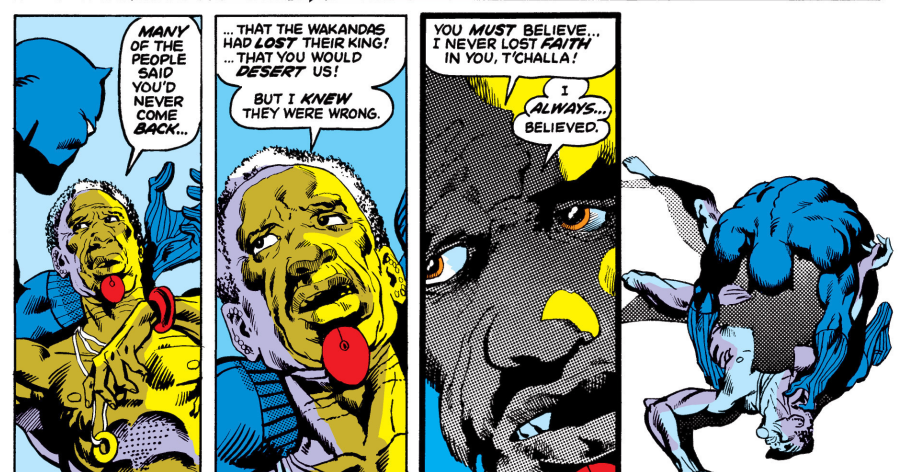

“Many of the people said you’d never come back…

“…that the Wakandas had lost their king!…that you would desert us!…

“But I knew they were wrong.”

Carrying the body back to the village, T’Challa is forced to admit:

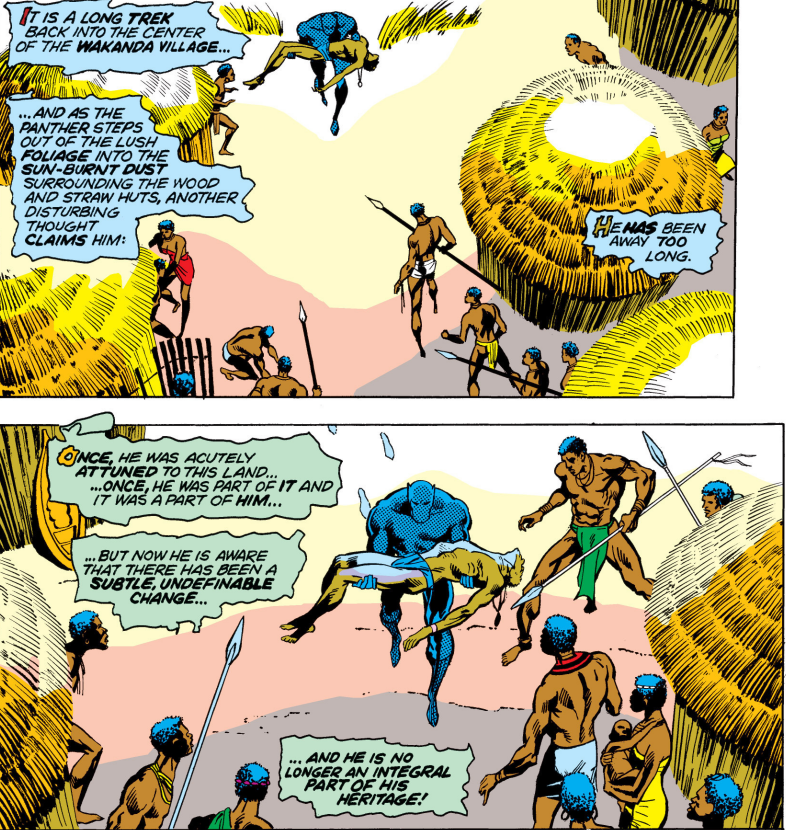

“He has been away too long.

“Once, he was acutely attuned to this land…once, he was part of it, and it was a part of him…

“But now he is aware that there has been a subtle, undefinable change…

“…and he is no longer an integral part of his heritage!”

Back at the palace, T’Challa finds no respite. His chief adviser, W’Kabi, has lost the faith that the dying old man had maintained:

“What tears at us is a whispered threat—that leaves terror in his wake! Erik Killmonger!

“Perhaps if you’d spent more time here, you would not have to ask!”

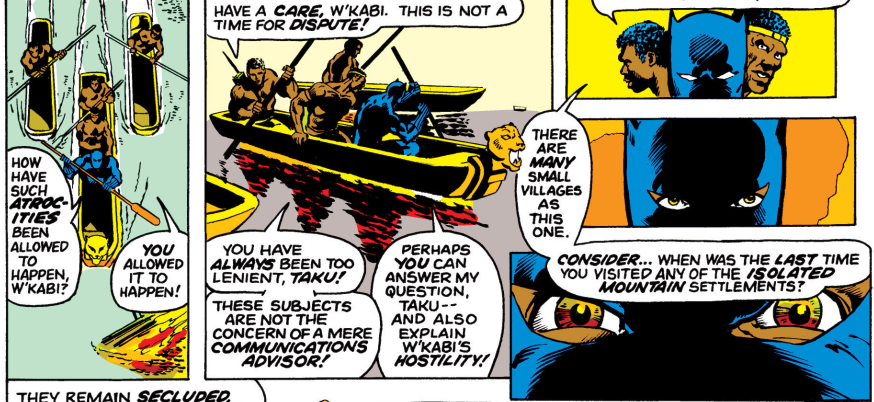

Thoughout “Panther’s Rage,” "W’Kabi is the voice of doubt, in contact to T’Challa’s more faithful communications advisor, Taku. Taku reprimands W’Kabi for blaming their king for the atrocities that have beset Wakanda, but even he cannot help but express gentle criticism of T’Challa.

“Wakanda expands, T’Challa!

“There are many small villages as this one,.

“Consider… when was the last time you visited any of the isolated mountain settlements?”

W’Kabi warns T’Challa that his country is on the verge of separatism: “are you strong enough to pull it back together?” The answer implicit within Jungle Action 6 is: no. It is fitting that the story ends not just in the Panther’s failure, but in his apparent death. From now until “Panther’s Rage” reaches its conclusion, T’Challa’s fight against the fragmentation of Wakanda’s civic body will be enacted in the continued assaults on the Panther’s own bodily integrity. In terms of politics, T’Challa does rather little to assuages his countrymen’s concerns (besides defeating Killmonger), but in a heroic fantasy such as “Panther’s Rage,” this is an easy thing to miss. Instead, T’Challa wages against his country’s disintegration in heroic acts of sympathetic magic, purging Wakanda’s conflicts through his own suffering and eventual triumph,

Note

[1] Both Christopher Priest and Ta-Nehisi Coates would start their runs on Black Panther with Wakanda on the verge of civil war.

[2] One of the many ways in which “Panther’s Rage” subverted convention was to have the insider/outsider conflict not be a problem of race or “miscegenation;” to follow the story, readers had to internalize the fact that being Black does not universally confer identity or commonality. Black or not, for many Wakandans Monica was a foreign interloper not to be trusted.