Monsters on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown

“The Kids Night Out” deployed Man-Thing’s empathic abilities more radically than ever before, transforming his usual, impulsive reactions to momentary emotions into a sustained cathexis with both Edmond and Alice. The intensity of these bonds may well explain why Gerber goes out of his way to shoehorn this story within the first few pages of Man-Thing 17. The splash page shows the Man-Thing mindlessly observing the aftermath of the carnage that ended the previous issue, followed by a second splash page summarizing “The Kids Night Out,” which we now learn took place the very next day (and resulted in Alice’s admission “for observation in the city’s already overcrowded mental health facility"). A few pages later, we discover that she is not the only emotional casualty of the day’s events. A three-panel pages is devoted to the depiction of a paralyzed Man-Thing:

“At swamp’s edge, Man-Thing stand trembling, his empathic nature battered insensate by the past days’ events.

“A creature not of intellect but of emotion—a being who feels what others feel—

“—but who cannot suppress or reason away these feelings as humans can—

“—he has finally reached a point of emotional saturation.”

A symbolic two-page spread renders his plight literal:

“All his energies are focused within. Across the barren waste that once was his mind marches a strange and frightening procession fo expressionless images…a bizarre torchlight parade of the men, women, bases, and demons, the conglomerate of whose tortured emotions drove him to this cataleptic state.”

These include virtually the major and minor characters of Gerber’s run: Darrel the Clown, Richard Rory, and “countless others sho brought pain and sorrow to their lives…and thus to his.”

Man-Thing is found by hunters who shoot him, take him for dead, and dump him in the Citrusville Sewage Treatment Plant. Obviously, he is not dead, but his temporary incapacity is a fascinating move. Why bother giving a mindless creature a nervous breakdown? Because empathy, however much the series lauds its virtues, takes its toll. Even though so many of Gerber’s characters are self-conscious (and even self-absorbed), they also tend to be highly attuned to the emotional and psychological states of those around them. Man-Thing shares this last trait, minus the self-consciousness. Gerber’s characters are in constant emotional and ontological conflict with their surroundings, and their occasional withdrawal only highlights the burden of maintaining one’s selfhood in a world that ranges from hostility to absurdity.

Even in “death,” Man-Thing serves as a reminder of the importance of emotional bonds. Richard Rory, now a DJ at a Citrusville radio station, gets the phone call that Man-Thing has been destroyed, and races to the bathroom for privacy:

“There, Richard Rory, to whom the monster was almost a friend, feels the energy drain from his limbs….feels his defenses crumble…and breaks down crying, and miles away, in the liquid blackness, Man-Thing, too, begins to break down…into his chemical components.”[1]

Rory and Man-Thing have always had a strong connection, but now their role seem to be reversed: it is Rory who is the vehicle for expressing emotion, while Man-Thing lies inert. The bottom of the page consists of 6 silent panels, alternating between increasingly tight shots of a weeping Rory and images of Man-Thing floating in the sewer (at an increasing distance), A few pages later, Rory is covering a town hall that is rapidly devolving into a book burning, spearheaded by Olivia Selby, a crusader again the “filth” she has discovered in her daughter’s high school textbooks. As she sets fire to a book entitled “Hygiene,” the panels move from the book, to Rory’s face, and then to a disintegrating Man-Thing. Rory runs onto the stage to save the book and implore the crowd to stop. He acts on impulse, knowing he will get fired, but he cannot simply watch.

In a similar moment in a Gerber-scripted Guardians of the Galaxy Story (Marvel Presents 4), new team member Nikki impulsively steers the Guardians ship headlong into cosmic monstrosity that has destroying a planet. Yondu, the Guardian with the strongest spiritual inclinations, calls this entity “Karanada—‘the emptiness that devours.’ It is total paralysis, not merely in the limbs—but the soul itself.” He justifies Nikki’s rash action: “She did as her spirit bade her […] No act of spirit can be wrong against Karanada.” Yondu’s words could apply to Rory, and, further, to all the most heroic moments in Gerber’s Man-Thing stories, Gerber’s characters tend to be intellectually savvy and, with the exceptions of the mindless and the mute, they have an excellent way with words. But they are at their best when they are moved by emotion. In other words, when they act like Man-Thing. Man-Thing is an externalization of their better natures.

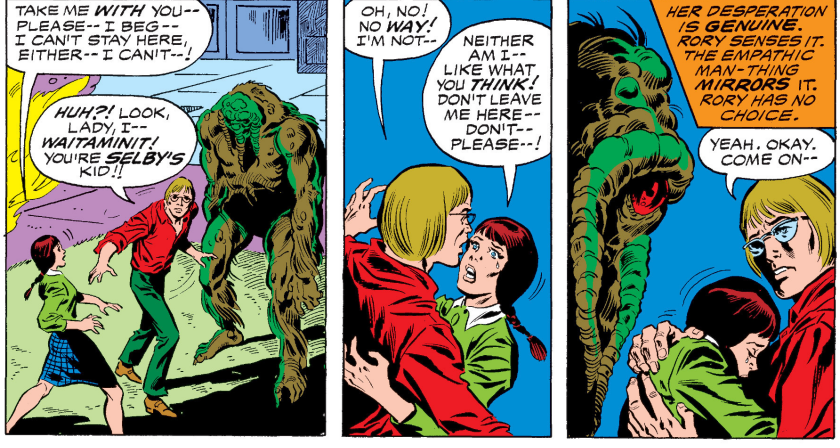

Richard Rory was introduced in Man-Thing 2 as the proverbial sad sack: everything bad always happens to him. But as the series progresses, it gets harder to see Rory as a passive victim. Bad things do happen to him, certainly. Not only is he fired after he tires to halt the book burning, he is also knocked out by the Mad Viking. The reason they happen, however, is that the only thing passive about Rory is that he is helpless in the face of an ethical conundrum: his moral compass and profound empathy give him no choice but to act. Even before the Mad Viking story is over, Rory finds himself agreeing to help someone against his better judgment. Carol Selby, Olivia’s teenage daughter, begs Rory to take her with him when he and a no-longer-dead Man-Thing leave town:

“Her desperation is genuine. Rory senses it. The empathic Man-Thing mirrors it. Rory has no choice.”

Man-Thing was Darrel the Clown’s suppressed rage, but for Rory, he is the embodiment of empathy. More often than not, Rory’s Man-Thing-like reflexive response to human suffering will do him more harm than good. Certainly that is true with the decision to bring Olivia along; she is underage, and when they cross state lines, he will be convicted of kidnapping. But he will also remain true to himself, and to the virtues embodied by Man-Thing.

Note

[1] The phrasing here is a hallmark of Gerber’s writing. Gerber had a marked fondness for semantic syllepsis (or zeugma), with the different meanings of “breaks down.”