Sith Lords of the World, Unite!

An earlier version of part of this chapter was originally featured on plostagainstrussia.org, as Chapter Four. It was not included in the final manuscript.

Among the many proxy battlefields that took the place of armed superpower conflict during the Cold War, we should also count the war for the popular imagination. When it came to “good guys” and “bad guys,” the Soviet Union after World War II specialized in only one type of story: the fight between the Soviets and the Nazis. This story structure proved both powerful and productive, and remains one of the primary filters imposed on Russia’s post-Soviet struggles. We see this in the post-Maidan conflicts in and with Ukraine, as I discuss at some length in Chapter Six of Plots against Russia: the enemies of Russia inevitably become the “fascists.” It was, however, of limited utility for framing the Cold War when the Soviet Union still existed, and of virtually none after the USSR’s collapse. And, like American stories of the fight against Soviet espionage or expansionism, it did not travel well to the other side.

American and European dualist dramas, on the other hand, were context-independent, or rather, in depicting fantasy worlds, they carried all the context they needed with them like a snail carries its shell. Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, and Harry Potter have captured audience’s imaginations the world over, and all of them are Anglo-Saxon story worlds based on the struggle between the forces of good and the forces of evil (with only the Harry Potter series treating the subject matter with any attempt at nuance). As such, they treat themes that could reasonably be considered universal. After all, what culture manages to do without stories about heroes and villains? Ideally, fantasy gives us virtual worlds which we can inhabit regardless of our background and baggage. Everyone can be Luke Skywalker or Frodo Baggins, because no one actually is Luke Skywalker or Frodo Baggins.

The problem is that the very last people who can determine what is universal and what is specific about such stories is the Anglo-Saxon audience. In the case of Russian audiences, we have, as is so often the case with late- and post-Soviet interactions with global popular cultures, a delicate question of timing. Tolkien, as we shall see, makes some headway in the USSR in the 1970s, much more in the 1980s, and is already a mass-culture juggernaut by the time Peter Jackson’s first installment of The Lord of the Rings appears in 2001. Star Wars was not available in the USSR in the 1970s, though it was frequently discussed (and reviled) in the Soviet press; the first two films were popular bootlegs when videocassettes became available, and were screened at a two Soviet theaters in 1988, with spotty distribution of the films throughout the 1990s (by which point they had already saturated the VHS market). The post- Cold-War Harry Potter comes to Russia with virtually no time lag whatsoever. Western fantasy’s capture of the Russian popular imagination coincides with the decline of the Soviet Union and the chaotic 1990s.

It is fitting that the entanglement of Western mass fantasy and Cold War politics should be highlighted by America’s Hollywood president, former cowboy actor Ronald Reagan. On March 8, 1983, Reagan gave his notorious “evil empire” speech, named after the phrase he used to describe the Soviet Union, in which he called on his countrymen to commit to the fight against communism as a “struggle between good and evil.” Fifteen days later, Reagan announced the Strategic Defense Initiative, immediately ridiculed as “Star Wars.” Two months after that, George Lucas concluded his trilogy with Return of the Jedi.

Conservatives lauded Reagan for bringing moral clarity to the superpower conflict, making clear to his countrymen that there was nothing ordinary about the ideological clash with the USSR. Liberals ridiculed him for endorsing a simplistic worldview that was likely to turn a Cold War hot. In fact, Reagan’s rhetoric was a departure for American mass media and culture. Despite the enduring caricatures of Soviet villains in spy stories, the more liberal-leaning Hollywood (which nevertheless managed to produce the right-wing Reagan) preferred stories that humanized the Soviets rather than demonizing them. Norman Jewison’s 1966 film, The Russians Are Coming! The Russians Are Coming! portrayed both the Soviet and American characters as flawed, lovable doofuses who, eventually working together, manage to to avoid bringing their two countries to all-out war.

Even popular science fiction and fantasy with explicit Cold War parallels often pushed its audience towards a more nuanced understanding of the enemy. The Klingons of the original Star Trek series were an obvious Russian stand-in, but at least one episode (1968’s “The Day of the Dove”) pushes the two sides towards a peaceful resolution of their conflicts. When the series was revived as Star Trek: The Next Generation, the Klingons were now the Federation’s allies (granted, they were also now culturally closer to stereotypes of the Japanese).

Reagan’s use of the term “evil empire” was part of a call for his country to re-commit to binary, black-and-white thinking, but couched in language that pointed beyond politics and even metaphysics: the phrase “evil empire” invites its listeners to understand their world in terms of fantasy. We now reach a strange convergence of genre and high theory: Lacan’s and Zizek’s identification of ideology as a form of shared fantasy and Reagan’s notorious slippage between fiction and fact. The Soviet Union as an enemy was not just real, but complicated, in a way that no amount of world building could complicate Mordor or the Galactic Empire. This is not to say that all fantasy is as simplistic as Reagan’s “Evil Empire” speech; Reagan needed the straightforward morals of Lord of the Rings, not the messy ethical compromises that, decades later, would be the hallmark of Game of Thrones.

Note

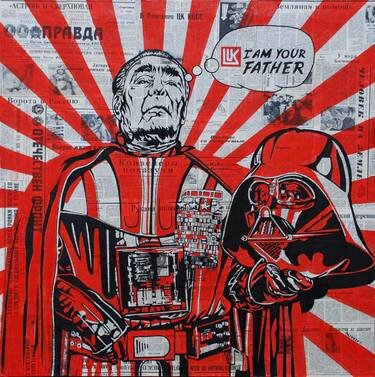

The Brezhnev/Vader image is a painting by Stanislav Belovski.