Super-Frenemies: Grant Morrison vs. Watchmen

One of the more obvious and least original complications Watchmen brings to the superhero genre is its rejection of the hero/villain binary at the heart of so many DC and Marvel sagas. Adrian Veidt commits atrocities for what he perceives to be the greater good while playing with some of the standard tropes of super villainy; after explaining his master plan to Rorschach, Nite-Owl and Silke Spectre, he tells them that he’s not “some Republic serial villain” giving away the key to his defeat before he can implement his plans; he already destroyed midtown Manhattan thirty-five minutes ago.

So how ironic is it that Alan Moore, the man whose work at DC started the “British Invasion” of American comics, has for decades been the object of a largely one-sided feud with the second most famous invader from the UK, a writer whose own ingenuity and accomplishments are slightly tarnished by his embarrassing animus towards Moore? The Scottish-born Grant Morrison has been picking fights with Moore since the 1980s, while Moore only occasionally responds with a withering remark.

EGO? WHAT EGO?

This is not the place to explore the Morrison/Moore psychodrama; anyone interested in their oddly parallel careers is directed to Elisabeth Sandifer’s outstanding book/blog series The Last War in Albion, which examines the two men’s careers in painstaking detail. This feud was easily avoidable: the field was, after all, big enough for the two of them (and more). Their work has a great deal in common: they’re both obviously postmodern, and each of them is fascinated with the artistic potential of the comics form itself. Each of them has dabbled in metafiction (Morrison more consistently), and each is comfortable with a variety of genres. And both of them are among the best writers working in the medium.

But there are also clear differences. Where Moore has all but abandoned the superhero genre, Morrison continues to explore its potential. Morrison has managed to move back and forth between best-selling runs of corporate superhero comics (JLA, X-Men, Superman, Final Crisis) and creator-owned projects (The Invisibles, Happy, The Filth), while Moore’s rare forays into other writers’ sandboxes have become events in themselves (Crossed +100), a stamp of the master’s approval.

I FOUND THIS BOOK IN A ROCKET SHIP FROM KRYPTON

In 2011, Morrison wrote a nonfiction book about superheroes entitled Supergods, which is a typically Morrisonian combination of insight and self-aggrandizement. It includes a reading of Watchmen that starts out far more positively that I would have expected. Morrison credits Moore’s and Gibbons’ work with “chang][ing] the way readers looked at superheroes forever,” and lays out a convincing close reading of the first chapter. His critique of Watchmen’s realism is equally compelling: “I liked superhero comics because they weren’t real”:

For all its pretensions to realism, Watchmen laid bare its own synthetic nature in every cunningly orchestrated line, lacking in any of the chaos, dirt, and non sequitur arbitrariness of real life. This overwhelmingly artificial quality of the narrative, which I found almost revolting at age twenty-five, is what fascinates me most about it now, oddly enough.

The Watchmen characters were drawn from a repertoire of central casting ciphers to play out their preordained roles in the inside-out clockwork of its bollocks-naked machinery. Moore’s self-awareness was all over every page like fingerprints.

It is not surprising that Morrison would eventually challenge Moore on his own territory and build a better Watchmen. What is surprising is the extent to which he succeeds.

Sons of Atom

Morrison has attempted a fictional response to Watchmen on two occasions, and each time within the context of a pandimensional, metafictional crisis that threatens the entire DC comics multiverse. His first riff on Watchmen comes as almost an aside in his 2008 Final Crisis miniseries and tie-ins. In the two-issue Superman Beyond, the title character travels to Limbo in order to obtain the substance that will bring Lois Lane back from the brink of death. Among the characters he encounters are three different variations on his own story: the Nazi Overman (whose Kryptonian rocket landed in the Sudetenland rather than Kansas); the aggressively evil Ultraman (his double from an anti-matter universe), and Captain Adam, a giant blue man with quantum/nuclear power, a fourth-dimensional perspective on time, and a tendency towards elliptical pronouncements.

A LITTLE SUPERMAN GOES A LONG WAY

Captain Adam (a variation on both Doctor Manhattan and his prototype, the Charlton hero Captain Atom), realizes that the only way out of the semi-fictional universe in which they are trapped is to harness the combined essence of both Superman and Ultraman:

“A new fusion processed powered by…”

“Dualities?”

“No. There are no dualities.”

“Only symmetries.”

This is both an allusion to Watchmen’s “Fearful Symmetry” and a statement about surmounting the conventional dualities of the comic book world in which the live (“Hate crime. Meet selfless act.”)

In Superman Beyond, Captain Adam is both plot device and thesis statement, but either way, his minor role is the inverse of his giant size. It is worth noting, however, that our introduction to Morrison’s version of Doctor Manhattan is part of an examination of the threats to the healthy existence of a fictional universe (or multiverse), and that the resolution to the overall plot requires that the characters come close to realizing that they are in a comic book. [1]

DUDE, IT’S JUST THE SHROOMS

Though this is a common enough Morrisonian theme (with his Animal Man looking at the reader during a peyote trip and shouting “I can see you!”, or the use of “fiction suits” to travel to other stories in The Invisibles), the emphasis on comics within comics is also a connection to Watchmen. Recall that one of the ramifications of the graphic novel’s is an ironic confirmation of Frederic Wertham’s fear-mongering about comics: the combination of frightening words and images (i.e., comics) drives New Yorker insane. If Watchmen is commonly considered a “deconstructive” take on the superhero comic, Final Crisis is reconstructive. It is also a fictional variation on the claim Moore makes on behalf of fantasy in Supegods: it’s good because it isn’t real.

The Multiversity’s Eternal Student

When Morrison returns to Captain Adam (who is really as much Morrison’s creation as Doctor Manhattan is Moore’s), he devotes an entire issue to his revision of Watchmen, this time as part of cosmos-spanning miniseries that doubles down on the role of comics within comics: this is the Pax Americana (2014) issue of The Mutliversity (2014-2015).

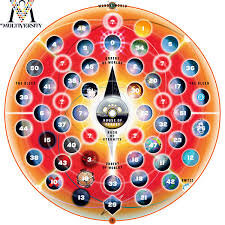

Though Pax Americana is the only one of the nine issues explicitly responding to Watchmen, the entire series shares Watchmen’s emphasis on structure and form. The pre-Crisis DC multiverse was usually depicted as a series of Earths overlapping with each other, a design that Morrison would make look rather pedestrian. Previously, Morrison had established that the known DC Multiverse was centered around 52 earths assembled in an elaborate “Orrery,” carefully monitored by beings known as Monitors. [2]

IT’S ALL QUITE SIMPLE, REALLY

The Multiversity series itself is a kind of mini-Orrery, but its very form renders it vulnerable to the threat of cosmic parasites calling themselves the Gentry. The Gentry invade each earth (that is, each comic) with their secret weapon: a comic book that serves as a plague vector disrupting the host world’s reality. In a comic book world, Ultra Comics 1 serves as a Trojan horse, if we imagine a Trojan horse as a metafictional vessel for nihilistic memes.

APPARENTLY, THERE’S A MONSTER AT THE END OF THIS BOOK

Watchmen was a work of metafiction in which comics were ultimately destructive (the attack on New York), but where only two of the characters came close to realizing they were in a comic book: Doctor Manhattan, thanks to his fourth-dimensional “comic book vision”, and Adrian Veidt, through his use of multiple TV screens as a second-rate replica of Jon’s powers, as well as his repeated references to the genres in which his story takes place (Republic serial villains, action figures based on himself and his former comrades, and his abandonment of the logic of superhero conflict in favor of a hokey, faux-1950s sci-fi solution to the world’s problems).

Multiversity, by contrast, is entirely dependent on the mechanisms of comics metafiction for its plot. Morrison’s programmatic rejection of the “realism” often ascribed to 1980s-era Moore translates into a full-fledged comicbook metaphysics. As in such earlier Morrison properties as The Invisibles, the existence of multiple planes of existence never grants any particular realm the status of absolute reality (our own world included). The Multiversity is about a fight among multifarious fictions, a situation with which Morrison couldn’t be happier.

I Am An Infinite Loop

Among its many virtues, Watchmen is a marvel of thematic and formal consistency. Nearly everything about it reinforces the book’s argument about the superhero genre, the comics medium, and the dialectic of bystander (reader) and intervenor/vigilante (fictional hero). Watchmen comes close to an impossible ideal of the comic as fractal: every constituent part is a recapitulation of the whole.

Morrison understands this essential feature of Watchmen; or, in order to avoid pretending that I can read Morrison’s mind (“I see you!”), the Pax Americana comic is a textual machine that understands Watchmen exquisitely well. Like a Borgesian cartography that is just as large as the world it aims to map, Pax Americana argues with Watchmen by being Watchmen.

Or almost being Watchmen. Pax Americana is a parody of Watchmen, not in the Mad Magazine sense, but along the lines of Linda Hutcheon’s famous definition of parody as “repetition with a critical difference.”

We have had a hint of the problem of repeating Watchmen when examining Before Watchmen, and it will be unavoidable when we get to Doomsday Clock (whose constant repetitions and echos of Watchmen’s art and prose only highlight the project’s limits). Multiversity is about an invasive species that runs wild throughout fictional worlds in order to transform them into versions of itself, a process that repeats itself more benignly in Morrison’s own approach to Moore’s and Gibbons’ graphic novel. In Pax Americana, Morrison finds a way to colonize Watchmen’s form and content and still remain himself.

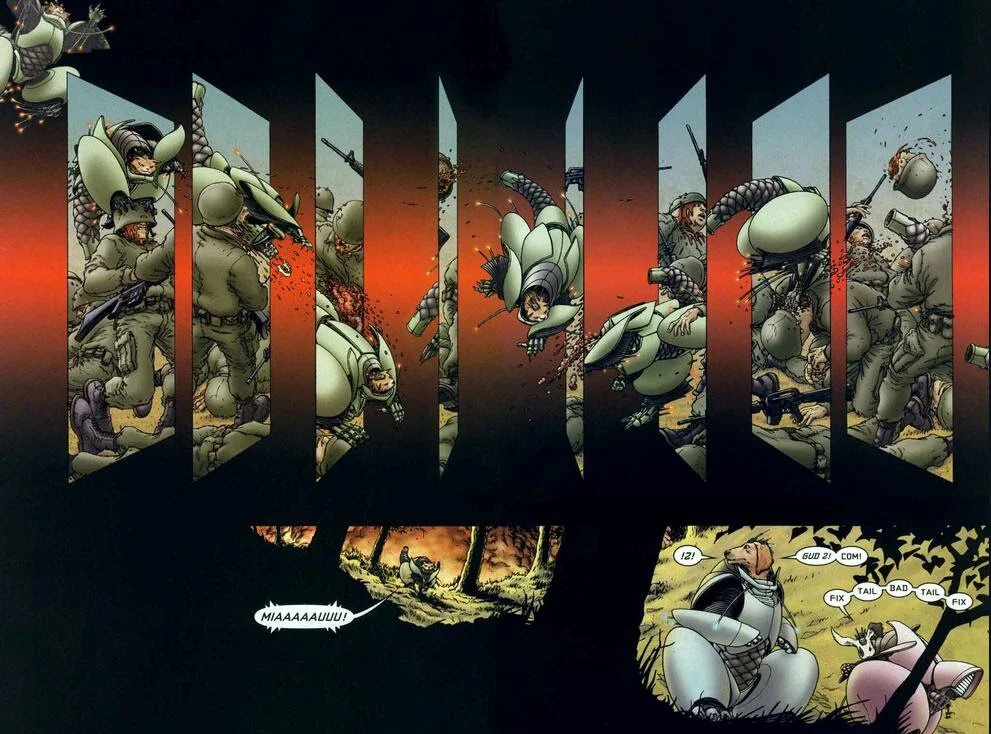

To cope with Watchmen, Morrison must swallow it whole. To do so, he creates Pax Americana with one of his best collaborators, the artist Frank Quitely. In comics such as We3, Quitely brought artistic innovations to match and even surpass Morrison’s writerly flights of fancy, such as in this two-page spread showing the cyborg animal protagonists seeming to move though the very materiality of the comics page as they rip apart the soldiers who have attacked them:

In Pax Americana, Morrison and Quitely do not take the obvious route of replicating Watchmen’s famous nine-panel grid (as Geoff Johns and Gary Frank will do in Doomsday Clock). Instead, they appropriate the notion of such a form by replacing it with an eight-panel grid. This may not sound all that innovative, but it works, because the number eight will prove to be the basis of Pax Americana’s own unity of form and content, a function fulfilled in Watchmen not by the grid itself, but by multiple variations on the smiley face that pops up on most of the comics pages.

In the course of Pax Americana, the concept of the number 8 and its visual manifestation (which is identical to a symbol of infinity) will replicate themselves at all level (the panel grid, the ring on the president’s finger, the mysterious algortihm, and, poignantly, the domino mask of a superhero’s who death thirty years ago haunts the entire story, but is only depicted on the final page).

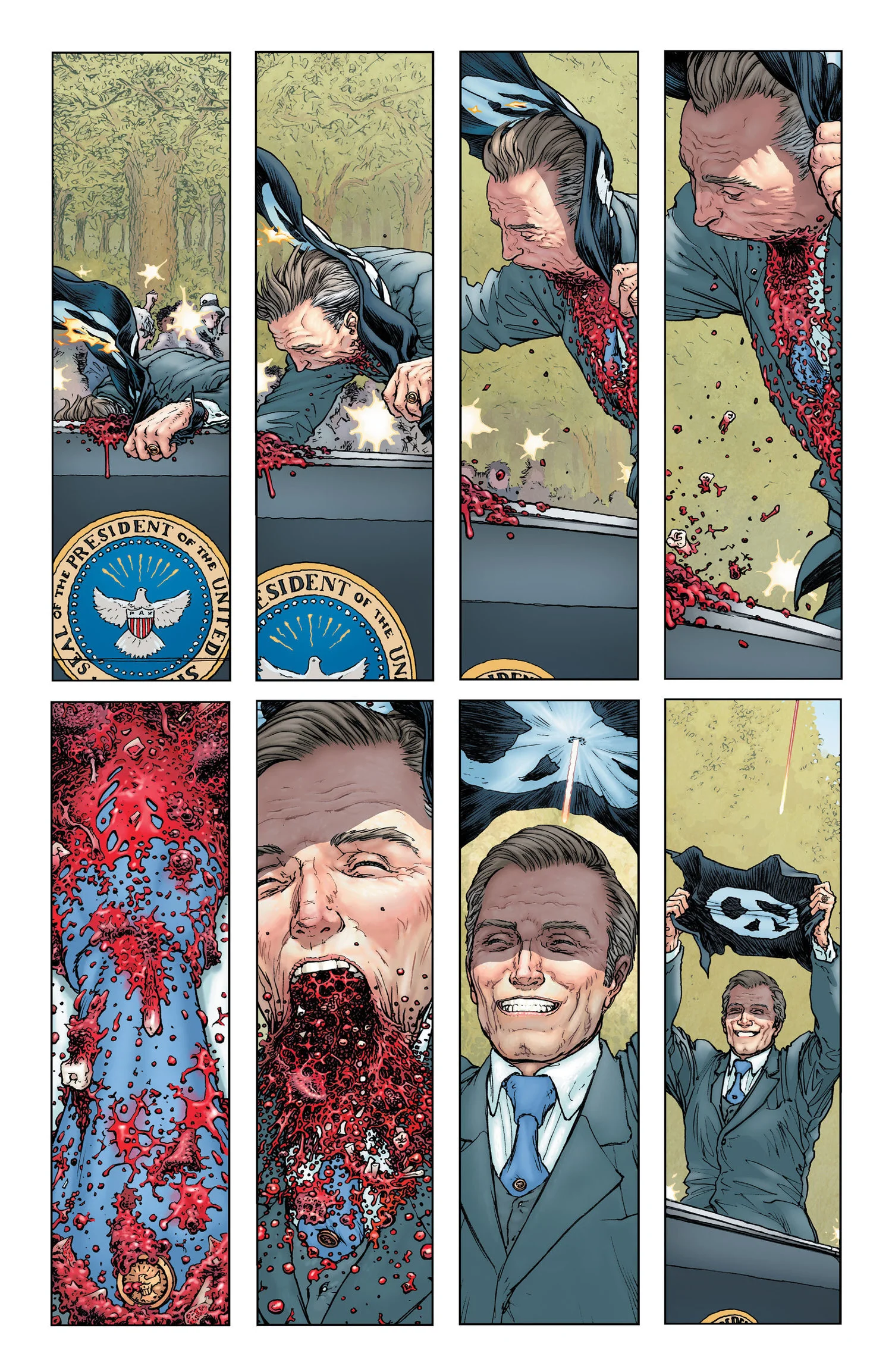

Thus Morrison and Quitely outdo Moore’s and Gibbons’ “Fearful Symmetry” at every opportunity. The comic is bookended by two murders, first that of the president (betrayed and yet not betrayed by the men who report to him), and then that of the superhero/comicbook writer Yellowjacket in an accidental shooting by his son, who will eventually grow up to be the president assassinated on page 1.

Watchmen offers the dubious comforts of non-sequential time: for Jon Osterman, any moment in his life is available for revisiting, but in exchange for this gift he loses his own sense of agency. Pax’s Americana opens with the promise of reversing time. Where Watchmen’s first pages are about a dead body and a murder, Pax Americana begins with the president’s bloody, disfigured corpse and proceeds to wind back the clock. Watchmen gives us the blood-stained smily face as its primal symbol, while Pax Americana’s president starts out missing his lower jaw. By the last panel on the page, the presidents’ face has been restored, and he bestows a toothy smile on his viewers.

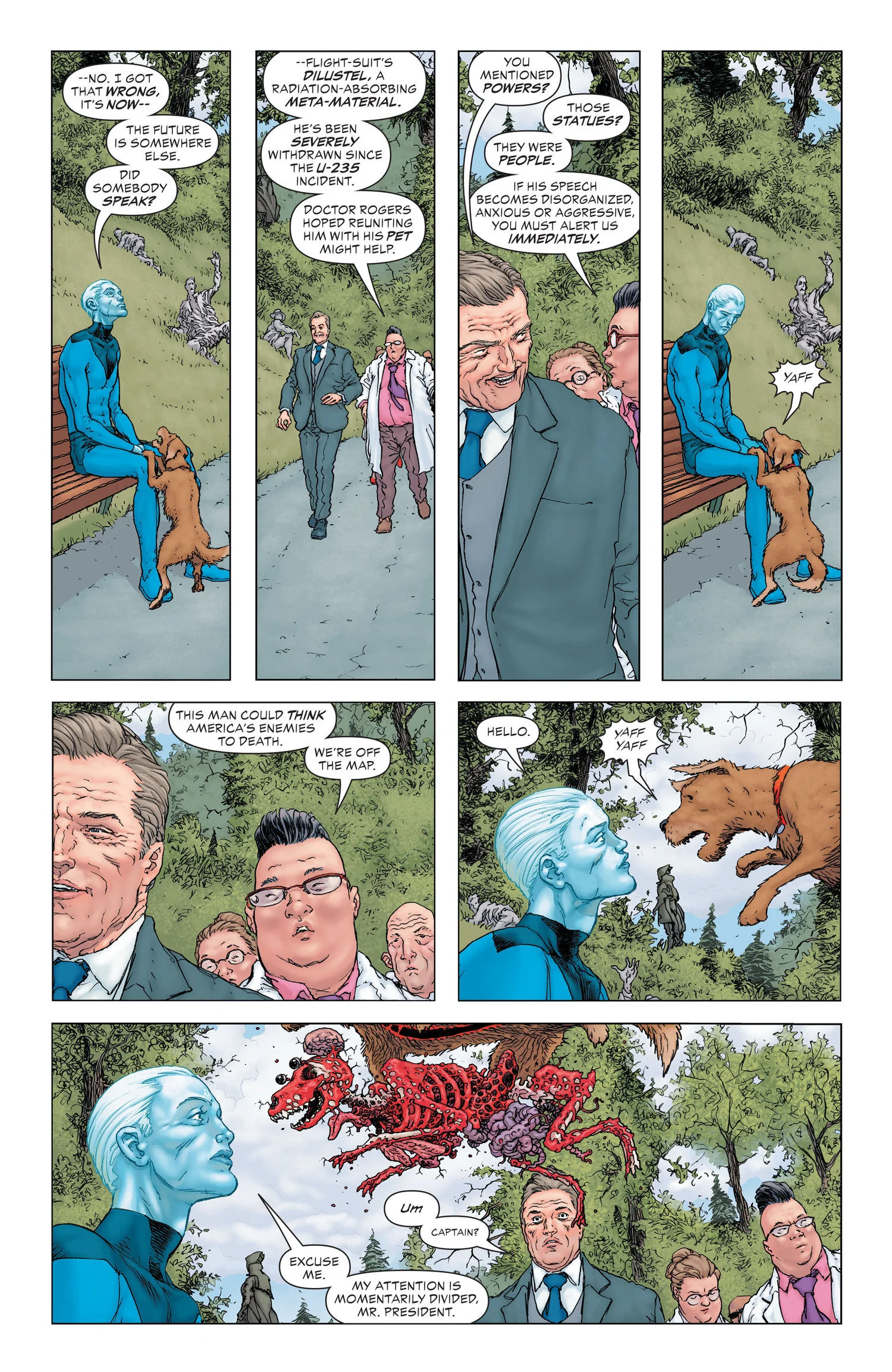

Watchmen and its variations each incorporates its own theory of physics: simultaneity for Watchmen, quantum physics and the superposition for Straczynski’s Dr. Manhattan series in the Before Watchmen project, and now Morrison gives us a comic whose initial accomplishment is the reversal of entropy. The entire comic revolves around various instances and promises of countermanding the Second Law of Thermodynamics: Captain Adam disintegrates his dog, only to rebuild him bit by bit (“It’s hard to love the pieces"), while the president arranges his own assassination in the belief that the Captain will do the same for him.

Pax Americana manages to be original by being unapologetically derivative. Like Adrian Vedit’s hero, Alexander the Great, cutting the Gordian knot rather than unraveling it, Morrison solves the problem of creative ownership and originality in a response to Watchmen that uses the hero who inspired Moore’s and Gibbons' characters. There is something wonderfully off-putting about reading a version of The Question who is clearly meant to be Rorschach, the character inspired by The Question. It is also instructive: by returning to the original source, Morrison shows us what Moore and Gibbons’ brought to the character, not how much they took from the original. But by putting these characters through a different comics mechanism, one with its own panel grid and its own approach to causality and time, Morrison and Quitely have created something that is more than merely a riff.

The DC projects that directly exploit Watchmen (Before Watchmen, Doomsday Clock) are trapped in an unimaginative fixation on the master text, a burden of influence that cannot be cast off in such a straightforward confrontation with the original. Morrison and Quitely prove that Watchmen can be a productive text if it is approached less as a set of specific, unchangeable character and plot points than as something akin to the founding work of its own new genre.

Notes

[1] Wonder Woman and the other Justice Leaguers store the entire world’s population in some shrinking/cryogenic procedure that turns them into the equivalent of a longbox full of comics, or a box full of action figures. Superman’s centrality to saving the day is based on his archetypal status as the inspiration for all the comic book heroes to follow him.

[2] The Monitor is a legacy concept from the 1980s Crisis on Infinite Earths. Where previously there had only been two (the Monitor and the Anti-Monitor), the 52 worlds of the post Infinite Crisis continuity had 52 corresponding Monitors. Final Crisis makes the Monitor census even more complex, but the particulars are not important for our purposes.

Eliot Borenstein 3 Comments1 Likes Share

Comments (3)

Newest First Oldest First Newest First Most Liked Least Liked Subscribe via e-mail

Preview POST COMMENT…

Anders Davenport 6 months ago · 0 Likes

“So how ironic is it that Alan Moore, the man whose work at DC started the “British Invasion” of American comics, has for decades been the object of a largely one-sided feud with the second most famous invader from the UK, a writer whose own ingenuity and accomplishments are slightly tarnished by his embarrassing animus towards Moore? The Scottish-born Grant Morrison has been picking fights with Moore since the 1980s, while Moore only occasionally responds with a withering remark.”

For a very comprehensive explanation of how Morrison went about manufacturing this feud with Moore, I’d recommend the series of articles called “The Reason Alan Moore Doesn’t Like Grant Morrison” – you can find the first one here:

https://tractorforklift.wordpress.com/2019/03/04/the-reason-why-alan-moore-doesnt-like-grant-morrison/

They contain numerous examples, including a breakdown of Final Crisis’ metanarratives and a bunch of quotes from Morrison regarding Pax Americana. In fact, Morrison has actually been doing riffs on Watchmen as far back as 1987 in his first mainstream creation, Zenith.

“Watchmen was a work of metafiction in which comics were ultimately destructive (the attack on New York), but where only two of the characters came close to realizing they were in a comic book: Doctor Manhattan, thanks to his fourth-dimensional “comic book vision”, and Adrian Veidt, through his use of multiple TV screens as a second-rate replica of Jon’s powers, as well as his repeated references to the genres in which his story takes place (Republic serial villains, action figures based on himself and his former comrades, and his abandonment of the logic of superhero conflict in favor of a hokey, faux-1950s sci-fi solution to the world’s problems).”

Very nice observation on Watchmen’s metafictional aspects. I’d offer that, in addition to what you’ve said, Watchmen also contains a comic-within-a-comic: the pirate comic read by the kid at the newsstand. The pirate comic not only parallels and overlaps with the narrative of the main storyline in Watchmen, but it also serves as commentary that comic books would be dominated by other genres in a world where superheroes actually exist.

Anish Fonseka 9 months ago · 0 Likes

I'm curious if you have any thoughts about the logistics of reading Pax Americana. The book was billed as an "experimental" approach to comics storytelling, and because of all the times a character in the book explores the concept of a Möbius loop, I tried reading the book backwards to front (like Japanese comics) as well. There were points in the book where the text and images flowed pretty logically and took on a whole new meaning. Of course there were also points where they made no sense, but this was also true, of portions of the comic, when I read it the traditional way. I wonder if this was a deliberate choice by Morrison or whether I simply missed something?

Eliot Borenstein 9 months ago · 0 Likes

Huh--I never thought to try to read it backwards! If it makes sense at all, that's quite impressive. I can't imagine even Morrison trying so hard to make it read well backwards and forwards, but who knows? Still, even if it is possible, I would guess that reading it in page order is still the best way to get the effect. After all, if watch the bullet hit the president and see his jaw fall apart, that's just excessive attention to bloody violence. But watching it backwards (i.e.., in the order presented on the page) is something entirely different. Thanks, Anish!